Ever

the Twain Shall Meet

Mark

Twain in Bermuda

Of all

the artists who were inspired by Bermuda’s muse—Georgia O’Keeffe, Winslow

Homer, John Lennon, Andrew Wyeth, Moores both Tom and Henry, and Albert

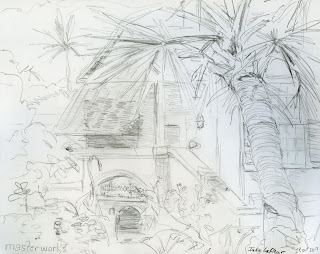

Gleizes, Mark Twain was Bermuda’s greatest advocate and ambassador. Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art together

with The Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, Connecticut celebrate

Clemens’ deep connection to the Island in “Ever

the Twain Shall Meet: Mark Twain’s Bermuda,” a special exhibit open through

June, 2014. With the exception of Wyeth,

visitors can see examples from all of the above luminaries at Masterworks upon

request, although they might find themselves too enthralled by Twain to tear

themselves away from this jewel of an exhibit.

Mark

Twain visited Bermuda eight times for a total of 187 days between 1867 and 1910.

Enchanted, he wrote "there is just

enough whispering breeze, fragrance of flowers, and sense of repose to raise

one's thoughts heavenward; and just enough amateur piano music to keep him

reminded of the other place....” Twain’s

writings extoll the peaceful beauty of the island (as well as its sometimes

dissonant charm) and were published between 1877-78 in The Atlantic Monthly as “Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion.”

A

treasure trove of objects is on display in Masterworks’ Mezzanine Gallery. Highlights include Mark Twain’s favorite pen,

his shirt (an integral part of his iconic white “dontgiveadamn suit”) and

a handwritten note from Clemens to one of his “angelfish,” surrogate

granddaughters whom he cherished for their innocence. The note reads, “It is far better to be a

young junebug than an old bird of paradise. You owe me a visit Dorothy, dear… Come — pay

up and save your character!” Without

being too heavy-handed, we urge you to visit Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art

to see the Island through Twain’s eyes, to bask in a literary paradise…to save your

character.